If the University of Rochester decided to determine its Mount Rushmore of collections, the William Henry Seward Papers would be a strong candidate, if not a shoo-in. That’s because it’s as exhaustive as it is extensive.

Held by the Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation (RBSCP), the Seward Papers is Rochester’s largest—and most cited—collection, comprising roughly 150,000 items and 350,000 pages. Its breadth and depth of materials, uncommon among archival collections from the same period, include pamphlets and books; political and personal correspondence; photographs, scrapbooks, and memorabilia. The majority of these materials were given to the University upon William Henry Seward III’s death in 1951, and there they remain frozen as the main collection.

However, that doesn’t mean the collection has stopped growing.

A somewhat serendipitous acquisition

In addition to the Seward Papers’ main collection, the RBSCP also maintains a living collection. The Seward Papers curator Autumn Haag, assistant director of RBSCP, has various “Seward alerts” set up to notify her of potential acquisitions. But one of the collection’s most recent additions, a manuscript letter from Confederate spy Rose O’Neal Greenhow to Secretary of State William Henry Seward, was the result of a tip from Emily Lapisardi, organist and choir director for the Most Holy Trinity Catholic Chapel at West Point.

Months prior, Lapisardi, also an accomplished musician, actress, director, and author, contacted Haag to research her now-published book Rose Greenhow’s My Imprisonment: An Annotated Edition.

“I was actually looking for [the Greenhow] letter,” says Lapisardi, “which, to my knowledge, none of the previous biographers had seen.” Of course, Haag didn’t have it. What she did have was some letters from Greenhow’s daughter, Florence, to Seward. Lapisardi thought the letters were “so interesting” that even though they didn’t directly pertain to the book, they deserved mention in an appendix.

Right after her book went to press, as if she were the target of an elaborate prank by the Universe, Lapisardi found the original letter on an auction site. She let Haag know.

The RBSCP bid on and won the letter, which it could do because of the FHA Seward Fund. “We’re very lucky to have an endowed fund specifically for materials related to William Henry Seward,” Haag says.

How dare you: A letter

For those who are not Civil War buffs, Rose O’Neal Greenhow was a socialite who turned Confederate informant. She was extremely well-connected politically and socially, traveling in powerful Washington, D.C. circles. But her known Southern sympathies led to her being watched closely by the Union and, ultimately, placed under house arrest.

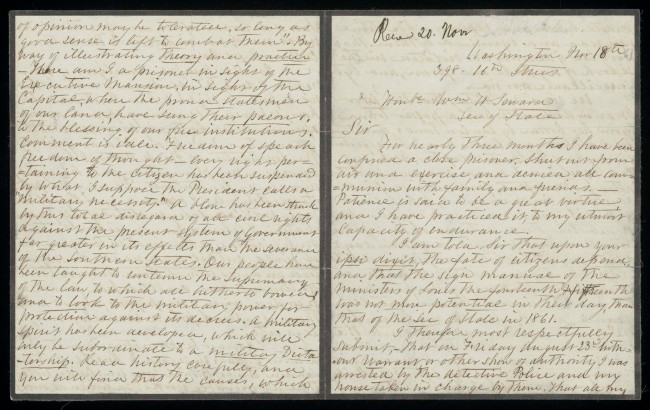

From Greenhow’s perspective, her imprisonment was an insult of the highest order. She expressed her indignation in an intensely melodramatic, eight-page screed to Seward that is both an airing of grievances and criticism of the government. Because the letter was published in the pro-Confederate Richmond Whig, Haag thinks the adversarial tone and theatrical language were for show.

“She’s playing the political game,” Haag says, “Her other letters [to Seward] are more polite—‘Can you do this for me?’—more reminders that they’re in the same social circle. This letter wasn’t just written for Seward’s eyes; it was for a much wider audience.” And a more sympathetic one, which is likely why a section of Greenhow’s letter went unseen by readers of the Whig.

The paragraph reads as follows:

My own convictions are that the only chance of our ever again being one people is in the capacity of the South to maintance [sic] herself. Then negoations [sic] can be entered into for adjustment which can bind us together stronger than ever. —Not as a conqueror or conquered But as brothers who have quarreled and are willing each to yield something for the b(l)essings of fraternal intercourse once more.

Lapisardi suspects the omitted paragraph could have been the doing of the Whig or Greenhow, for essentially the same reason—it would not be well-received. “It’s opening up the possibility of some sort of peaceful relations,” she says, noting that Greenhow did not include the paragraph when she reprinted the letter in her book, published in England in 1863. “The letter is really striking because it shows her to be a very politically and historically savvy person.”

Vintage Greenhow

In the RBSCP blog, Haag writes that the excitement of a new manuscript “can be tempered by the realization that its creator had less than perfect penmanship.” Lucky for Rochester, the manuscript copy of the Greenhow letter was accompanied by a transcript, which can be read in its entirety in Haag’s blog post. Should you need some coaxing, we put a spotlight on some of Greenhow’s hammier passages. And because she fancied herself a member of high society, they’re presented as “fine wines.”

Furieux Rosé

“We read in history, that the poor Maria Antonette [sic] had a paper torn from her bosom by lawless hands, and that even a change of linen had to be effected in sight of her brutal captors. It is my sad experience to record even more revolting outrages than that…”

Pairs well with: Asking to speak to the manager.

Notes: Bold and ironic. Greenhow comparing herself to France’s most well-known queen speaks volumes about her opinion of herself. But what makes it so audacious is she was still doing spy stuff. “She’s not an innocent victim,” says Haag. “She was still getting letters snuck out. She hadn’t stopped her work.”

Überzeugung Riesling

and her daughter, Rose

“You may subject me to harsher ruder treatment than I have already received. But you cannot imprison the soul. Every cause worthy of success has had its Martyrs.”

Pairs well with: Holding your breath.

Notes: Full-throated, artificial, and yet, triumphant. You can almost envision Seward rolling his eyes here. And again, she is guilty, a fact that ended up being her demise and earning her martyrdom. Not long after her release from house arrest, she went to England to raise money and support for the Confederacy. On her return to the U.S., her ship was blockaded. When she attempted to reach shore in a rowboat, she fell out and ended up drowning. A common legend says it was because of the gold bars sewn into her dress. The gold was actually in the form of coins, and they were in a pouch, weighing around six pounds, around her neck. Her clothes likely weighed her down more than the gold. None this really matters if she didn’t know how to swim, as Lapisardi suspects.

Tradimento Valpolicella

“I believed your success a virtual nullification [sic] of the Constitution, and that it would entail upon us the driful [sic] consequences which have ensued. These sentiments have doubtless been found recorded among my papers, and I hold them as rather a proud record of my Legacity [sic].”

Pairs well with: The saddest violin music you can find.

Notes: Bitter. Lapisardi calls the letter a moment in time in which allegiances were changing. “Although [Greenhow and Seward] were, politically, holding very different positions, they had been close friends,” says Lapisardi. “It really shows how these old political friendships were transformed by the war, how that friendship has turned.” ∎

To learn more about this letter or other parts of the William Henry Seward Papers, contact collection curator Autumn Haag at ahaag@library.rochester.edu. If you’re interested in supporting the growth of the Seward collection or other collections held by Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, contact Pam Jackson, senior director of advancement for the River Campus Libraries, at pamela.jackson@rochester.edu.

Enjoy reading about the University of Rochester Libraries? Subscribe to Tower Talk.