First-time visitors to the Rossell Hope Robbins Library at the University of Rochester won’t be surprised to find stacks of books from its comprehensive holdings on history, literature, art, and culture from the Middle Ages. And although it’s unlikely they will expect to find a full-sized recreation of a 16th-century book wheel—which they will—it won’t appear out of place in a medieval studies library. What may be most remarkable is that the space is a veritable art gallery.

Robbins, located on the fourth floor of Rush Rhees Library, is also home to the Koller-Collins Center for English Studies. Its walls are covered in artwork. Various paintings, watercolors, lithographs, etchings, and drawings give the space the warmth and grandeur of a medieval aristocrat’s extensive private library. But there was never a lord; there was Russell Peck, a professor emeritus of English and the John Hall Deane Professor Emeritus of Rhetoric and Poetry at Rochester.

Peck, who died on February 20 this year, was an eminent medieval scholar and one of the driving forces behind Robbins’ creation.

In a story honoring his memory, Anna Siebach-Larsen, director of the Robbins Library and Koller-Collins Center, says, “The library’s existence is a testament to Russell’s far-reaching vision, indomitable will, and commitment to a generous and capacious ideal of scholarship, teaching, and fellowship.”

That characterization of Peck very much extended to the library’s décor.

When resolve meets passion

Peck loved art. As an ardent patron of local galleries, including the University’s Memorial Art Gallery (MAG), and frequenter of MAG’s Clothesline Festival and Fine Craft Show & Sale, his home was full of pieces he acquired. Often, his collecting habits carried over to the Robbins Library and Koller-Collins Center.

When Peck found a new piece for the space, he’d grab a hammer and nails, maybe an electric drill, and hang the art himself—fully aware that University Facilities would not approve.

“He was very decisive and a little bit impetuous and didn’t really care about rules—at all,” Siebach-Larsen says. “He was really interested in making this a space of art, literature, and intellectual community, which is why he worked so assiduously to find pieces that would fit here.”

One of the last pieces Peck brought into the space came in December 2022. He emailed Siebach-Larsen telling her he had the perfect piece and knew exactly where it needed—needed—to go. It was a reproduction of Edwin Landseer’s Scene from “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” and it went over a kitchenette sink in Robbins.

‘A genealogy through art’

The Robbins Library and Koller-Collins Center has been full of art since opening in 1987. Some pieces came from Peck, but many were given by Rochester alumni and friends of the English department, many of whom he wrote to, encouraging them to donate specific works of art.

Siebach-Larsen emphasizes that Peck’s collecting wasn’t about curating an art collection but about memorializing a community whose members provided support through leadership, intellectual labor, teaching, or gifts.

“Many of the gifts are in memory of people,” explains Siebach-Larsen. “So, on the backs of a lot of pieces, there will be indications that someone gave the piece in honor of a faculty member or something like that. It’s like a genealogy through art on the walls.”

There’s the 19th-century lithograph of Lord Byron by Rembrandt Peale, made possible by Anthony Hecht, the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and professor emeritus of the English department, who made a bequest in memory of James Rieger, who spent many years as the University’s principal English romanticist. And Jerry Wnuck gave a print of Edmund Spenser’s poem The Faerie Queene, which hangs in the seminar room, in honor of Rieger.

An anonymous donor is responsible for the set of color etchings entitled Romeo and Juliet by the Hungarian artist Adam Wurtz, displayed in the mezzanine above the seminar room.

Sarah Collins provided a plaster cast of Alfred Lord Tennyson by sculptor William Ordway Partridge in memory of her husband, Rowland Collins, a University English professor and an authority on Anglo-Saxon literature.

“Having all of this art in the library is a reflection of Russell’s passion and dedication to the Robbins Library and its community,” says Siebach-Larsen. “We are a beautiful space because of the art, but the space would not be what it is without the people who have passed through our doors and cared deeply about their experiences here and the experiences of future generations.”

To further highlight some of the artwork within the Robbins Library and Koller-Collins Center, we asked a few staff members to talk about their favorite pieces—which happened to come from Honoré Sharrer and Jack Coughlin. .

Honoré Sharrer

The Judgment of Paris

chosen by Steffi Delcourt ʼ14 (MA), PhD candidate, English

Given by George Ford, a Rochester English professor, and his wife, Patricia, in 1988 in memory of Nicholas and Olga Konraty (the painting’s original owner who taught German at the Eastman School of Music), Sharrer’s depiction of the classic Greek myth was possibly Peck’s favorite piece in the space. He loved to give lectures about the painting, which comes through in his description of it in the University of Rochester Library Bulletin, Volume 40 (1987–88), where he writes that The Judgment of Paris

“depicts the three goddesses Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite in muliermorphic form enacting their separate versions of what they imagine to be alluring to the voyeuristic male judge who is himself something of an exhibitionist. The picture wittily satirizes male egotism as the women mock his expectations and thereby comically assert their independence.”

Delcourt’s appreciation comes from the delightful juxtaposition of odd and ordinary.

Delcourt says:

“It presents a wonderful combination of the mundane and the mythical, the fantastic and the everyday. I love that Sharrer plays up the absurdity of such a choice while still displaying the basic elements of the myth in her painting.

“The space around the goddesses is littered with everyday objects—an apple (looking more Golden Delicious than the myth’s original golden), a cupcake, a bent fork, even a razor blade in one of the corners—all of which add a sense of whimsy to a scene concerned with the decisions of gods and goddesses that led to the Trojan War—a contrast that Russell always loved. Russell was fascinated by how stories and myths and fairy tales are told and retold throughout time, and so I think that aspect of this painting really spoke to him.”

Saint Jerome

chosen by Emily Lowman, PhD candidate, English

Given by an alumna in recognition of the time she spent in the Robbins Library, particularly working with Peck, Saint Jerome features Saint Jerome, naked and withered with a lion—Lowman’s favorite aspect.

Lowman says:

“I’ve loved the lion since I first came to Robbins and Rochester. Typically, a predatory cat in his place would loom threateningly over the patrons below, but this lion is the most contented creature to possibly ever be painted. He is utterly and visibly blissed out beside Saint Jerome. The rest of the piece is interesting, certainly, and I’ve never run out of details to examine. The formally robed monkey, mysterious owl, menacing demon-samurai, and enigmatic hat with smoky tassels are all intriguing. But the feature I most often find myself appreciating is the lion.

“The piece fits the eclectic yet carefully curated vibe of Robbins—and Russell. It draws on artistic, scriptural, and literary traditions from a variety of backgrounds, and it prompts thinking, discussion, and no little debate. Russell’s heart was in all of these things. All in all, though, I think it represents a surprising take on an old subject. That is one of the most Russell things about this artwork. I’ll always associate him with twists on the familiar.”

Jack Coughlin

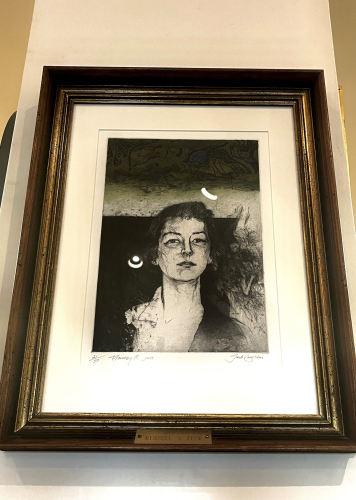

Flannery O’Connor

chosen by Anna Siebach-Larsen

This etching of Flannery O’Connor, given by Peck, is one of a series of lithographs and watercolors of American and British writers created by the Massachusetts artist. The space includes many portraits, including Emily Dickinson, Charles Dickens, Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, Edgar Allan Poe, Walt Whitman, and Virginia Woolf.

Peck worked closely with Nancy Buckett from Oxford Gallery in Rochester to bring the entire set of Coughlin portraits to the library. Siebach-Larsen explains that Peck wanted the series because he thought each piece was artistically interesting in the way it captured the personality of each writer.

Siebach-Larsen says:

“I chose this one because I particularly love Flannery O'Connor, and I think the etching itself is a really interesting and a striking one. And there’s a subtle link to Russell there.

“O’Connor was interested in exploring the different facets of human experience, especially the questions that force us to wrestle with faith and doubt. That’s a lot of what Russell explored in his work and classes.”

Emily Dickinson

chosen by Katie Papas ʼ98 (MA), the section supervisor

This etching was a gift from Anthony Hecht. Papas’s choice lives at the intersection of proximity and kismet. Studying Dickinson’s work at the University of Maryland made her want to pursue a master’s degree in English, which brought her to Rochester. On her first day working in Robbins, she noticed Dickinson’s portrait hanging outside her office door. Papas took it as a sign she was in the right place.

Papas says:

“One of my favorite things about Robbins is that there are many portraits of writers, including Lord Byron, Walt Whitman, and Toni Morrison. These representations are an important part of Robbins because they are a reminder that Robbins is more than a medieval library. Many of our users are students of literature beyond the Middle Ages, and the portraits that Russell chose to hang throughout are representations of the depth of the collections.

“As someone who came to Rochester to study modern American poetry—and whose interest leans toward the Koller-Collins collection—the portraits of these pivotal authors are beautiful visuals of the history of literature and a great reminder of how Russell, a scholar of the Middle Ages, was also a man whose fascinations could never be confined to one era or genre.” ∎

If you’re interested in learning more about the art in the Robbins Library and Koller-Collins Center, reading Russell Peck’s entry in the University of Rochester Library Bulletin is a good place to start. You can also reach out to Anna Siebach-Larsen. And if you have art you would like to donate, contact Pamela Jackson, senior director of advancement for the River Campus Libraries.

Enjoy reading about the University of Rochester Libraries? Subscribe to Tower Talk.