Before Beatlemania, there was Gilbert and Sullivan.

Between 1871 and 1896, librettist W.S. Gilbert and composer Arthur Sullivan produced 14 comic operas, including The H.M.S. Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance, and The Mikado. These operas, and others produced by Gilbert and Sullivan (G&S) were the theatrical events in England and America during this time.

Before this goes too far, one voice needs to be given priority. Hal Kanthor ʼ66M (MD)—not a major-general, but a G&S authority.

Hal is the very model of a G&S authority

He’s a lot to say theatrically, musically, and lyrically

He knows all fourteen operas, and he talks about them joyfully

From Pinafore to Ruddigore, in general generality

He’s more than well acquainted, too, with Gilbertian soliloquy

He lauds libretti that are full of fanciful absurdity

About the topsy-turvy worlds, he’s brimming with a lot of views

Some of which discuss the feat of rhyming with ‘hypotenuse’

On legacy and history, he’s more than just reliable

His collector bona fides are simply undeniable

In short, in matters theatrically, musically, and lyrically

Hal is the very model of a modern G&S authority.

Now that he’s been properly introduced, he can provide his expertise on G&S.

“When [G&S] first began working together, they were very well known in their own right,” Kanthor explains. “Sullivan was probably the most recognizable musician in England. And Gilbert was the preeminent dramatist of 1870s, writing 35 plays in a decade alone.”

Initially, the duo was “of the same mind.” The process would start with Gilbert writing the lyrics, and then it was Sullivan’s task to give them music. However, the partnership eroded over time. Sullivan soured on Gilbert’s style, and he “had a lot of pressure on him to write more serious music,” Kanthor says. “[Queen Victoria] expected him to be a serious composer.” The two parted ways in 1890.

But at their peak, they were living legends.

“They were treated like rock stars of today,” says Kanthor. “Newspapers would use their front pages to report the latest show opening. Cities were named after G&S operas. They created a sort of mass hysteria.” In that hysteria, the shrewd saw an opportunity.

Kanthor explains that many with something to sell quickly attached their products to G&S’s coattails. And that’s what enabled him to collect 19th-century ephemera, including programs, playbills, advertising trade cards, cigarette cards, photographs, and evens bars of soap. (Many of these materials can be seen in the digital exhibition Gilbert & Sullivan: From London to America.) He also has a diverse array of posters, which he gave to the University of Rochester.

The Kanthor Collection of Gilbert and Sullivan, held by the Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation (RBSCP), demonstrates how posters featuring various graphic designs were used for advertising specific productions and theatrical companies.

Reflections from the curator

At the end of June, Kanthor visited the River Campus to give a talk on Gilbert and Sullivan’s influence on 19th-century advertising, which referenced materials from the Kanthor Collection. The event was held in conjunction with the exhibition Ephemera: The Minor Transient Document of Everyday Life, which is on display in RBSCP through the end of 2022.

For anyone who couldn’t attend, Jessica Lacher-Feldman is here to offer her professional commentary on the Kanthor Collection. In addition to being exhibitions and special projects manager, Lacher-Feldman is also the curator of theater collections.

Hello, Jessica. Can you start by providing a brief overview of the theater collections?

Lacher-Feldman: RBSCP is home to a number of manuscript collections and published materials relating to theater and drama, primarily in the United States and Great Britain. It includes a vast collection of theater programs and playbills from the 19th century to the present day—with productions in Rochester, New York City, London, and elsewhere—as well as a significant collection of 20th-century British plays and a strong specialization in Restoration Drama.

The Harold A. Kanthor Collection of Gilbert and Sullivan is a celebration of the wonder of Gilbert and Sullivan’s productions and how these works have become part of our collective conscience over time. Working with Hal on this collection has been really exciting, as he adds to this rich collection regularly.

What do you most enjoy about working with the Kanthor Collection?

Lacher-Feldman: Having the privilege to work closely with Hal. He is always willing to impart information, enthusiasm, and materials for his collection, and I learn from him all the time. Working closely with a donor and collector is a true privilege for a curator, as it allows us to better serve the collection and those who use it. Working with Hal makes me a better curator.

Additionally, he has graciously guest-curated a few exhibits in RBSCP, and of course, there was the recent presentation on Gilbert and Sullivan’s influence on late-19th-century American advertising. Hal is also keen on working with his collection and has been integral in the processing work we do for the collection.

There is also a great deal of whimsy, humor, and joy in the Gilbert and Sullivan materials. One cannot help but be drawn to the art and design around the posters and other materials in the collection.

Let’s talk about the collection. Any favorite pieces?

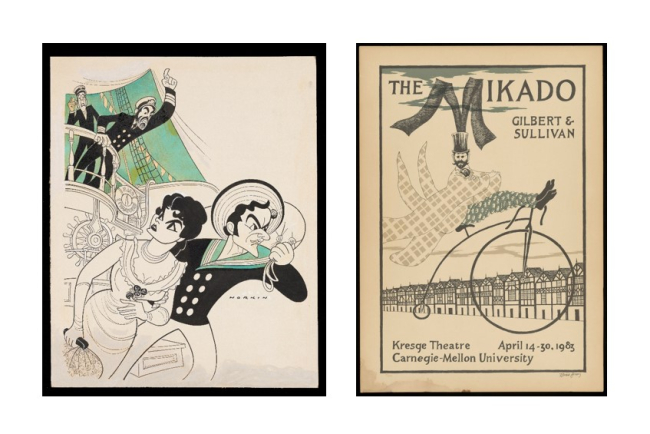

Lacher-Feldman: Three silk-screened posters designed by printer and artist Rex May in the 1960s are among the items that I love the most. The posters were designed for San Francisco’s Lamplighter Theater productions of Ruddigore, The Mikado, and The Gondoliers. May captures the spirit of these operas in his mid-century, modern design. For example, he cleverly uses gondolas as mustaches in the Gondoliers poster. Overall, their bold color and design, compelling graphics, and clever use of space are really compelling.

Any others?

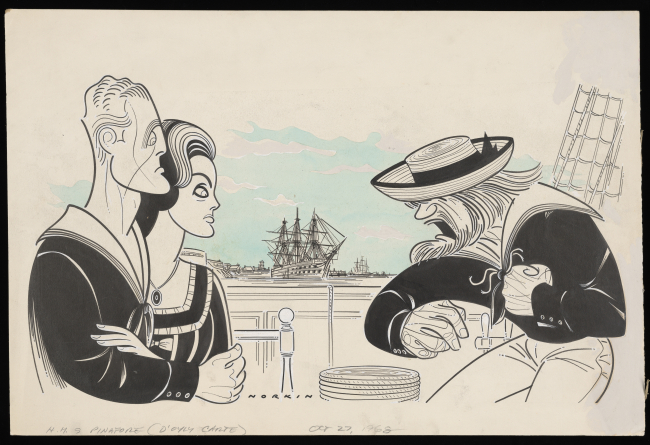

Lacher-Feldman: I am also drawn two beautiful original illustrations in the collection done by Sam Norkin (1917–2011). Norkin was a New York-born cartoonist who specialized in theater caricatures. His unique style is reminiscent of fellow theater caricaturist Al Hirschfeld. The Norkin illustrations are originals from the 1960s, both from a D’Oyly Carte production of The H.M.S. Pinafore, and you can see the white-out and corrections, along with his signature use of a really distinctive minty-green in both drawings, coupled with the sweeping black ink illustrations.

Finally—perhaps my favorite item—a 1983 poster for The Mikado, designed and signed by Edward Gorey (1925–2000). Gorey’s unmistakable pen and ink style, his use of Victorian-style imagery, and his play with pattern make this such an interesting poster. It’s also hard not to be drawn to the clever and bizarre adaptations of Gilbert and Sullivan operas, like Starship Pinafore or Zombies of Penzance! ∎

For more information on the Kanthor Collection or RBSCP’s theater collections, contact Jessica Lacher-Feldman at jlf@rochester.edu.

Enjoy reading about the University of Rochester Libraries? Subscribe to Tower Talk.