People across the country are being asked to stay at home to slow the spread of COVID-19. According to the New York Times, as of April 27, that request is still official in 41 states. Still, it’s only a request and a conditional one at that. If people need to leave their homes, say for groceries, they can, with or without a mask or face covering, depending on where they live. By 14th-century Europe standards, this is dangerously lenient.

Beginning with an outbreak in 1347 that remains unparalleled, the Plague (aka the Black Death, aka the Pestilence) haunted Europe for hundreds of years. So, when Marseille, France, incurred an outbreak of the bubonic plague, the city effectively went to viral DEFCON 1.

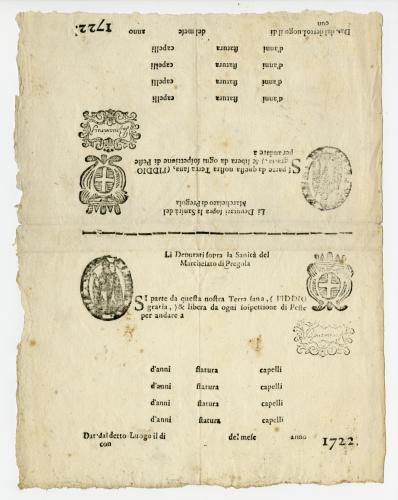

During the Great Plague of Marseille (1720–1723), travel between major cities wasn’t possible without a “bill of health.” For example, in 1722, if an Italian traveler from the Province of Pavia, Lombardy was trying to enter Marseille, they would have been carrying a patente di partenza or “bill of departure.” The History of Medicine section at the University of Rochester Medical Center’s Edward G. Miner Library, holds samples of two of these documents (pictured below), which were printed one leaf of paper. These documents were printed by the authority of the health deputies of the marquisate of Pregola. Roughly translated, the document says, “We depart from this our healthy land, (thanks be to God,) and free from any suspicion of Plague go to…” The traveler’s destination would be filled in the large space just below. Beneath that is where traveling companions would be listed along with their age (“d’anni”), height (“statura”), and hair color (“capelli”).

Meredith Gozo, curator of rare books and manuscripts for Miner Library, acquired the document in the fall of 2019 for the ephemera collection.

“We already have many books on the treatment of plague and other epidemics in the collection,” said Gozo. “What I love about this piece is how accessible it is. This little piece of paper that’s almost 300 years old tells us something about how European communities tried to prevent the spread of infectious disease.”

Gozo admitted she didn’t foresee the document’s contemporary relevance when she purchased it, but said it served as “a reminder that history has a way of repeating itself.”

For more information on this piece or other related material in the Miner Library’s collection, contact Meredith Gozo. Enjoy reading about the University of Rochester Libraries? Subscribe to Tower Talk.