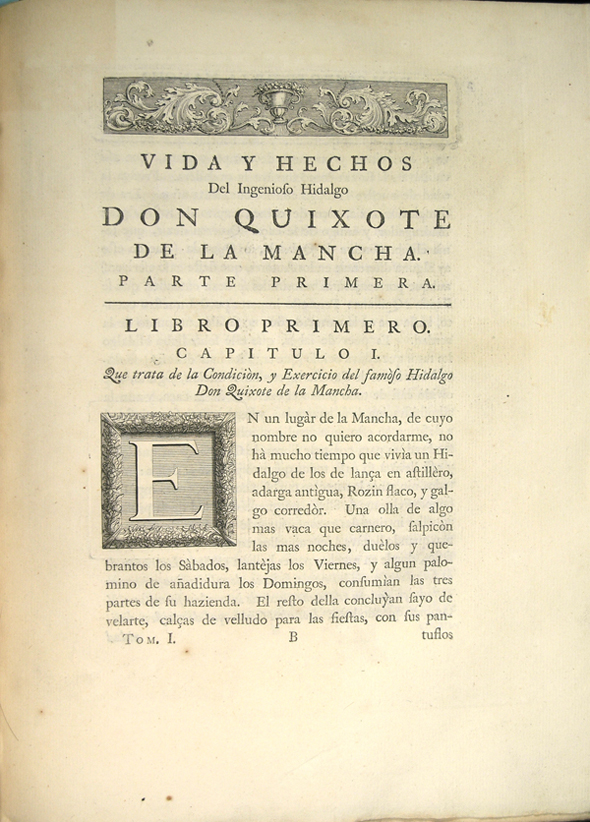

Vida y Hechos del Ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha. Compuesta por Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra. En Quatro tomos. London: J and R. Tonson, 1738.

This title represents a significant landmark in the printing history of Cervantes' Don Quixote: the first deluxe edition of the novel, and the first edition in Spanish published in England. It is a large quarto profusely illustrated with 69 copperplate engravings, including the first portrait of Cervantes and an allegorical frontispiece. The portrait was painted by William Kent and engraved by George Vertue. John Vanderbank designed 66 of the plates, and William Hogarth created one and part of another. The engravers of the plates were G. Vandergutch, B. Baron and Claude du Bosc.

Since there was no authentic painting or drawing of Cervantes, Kent composed one by following Cervantes' detailed self-description included in the preface to hisNovelas Exemplares:

"This man you see here, with aquiline face, chestnut hair, smooth, unwrinkled brow, joyful eyes and curved though well-proportioned nose; silvery beard which not twenty years ago was golden, large moustache, small mouth, teeth neither small nor large, since he has only six, and those are in poor condition and worse alignment; of middling height, neither tall nor short, fresh-faced, rather fair than dark; somewhat stooping and none too light on his feet; this, I say, is the likeness of the author of La Galatea and Don Quixote de la Mancha, . . ."

Shortly after the publication of the first edition of the first part of Don Quixote in 1605, illustrators and engravers attempted to reproduce both the characters and some of the most emblematic scenes of the novel. The first known illustration in the printing history of this book is a rough woodcut depicting Don Quixote, sword in hand, mounted on Rosinante, preceded by his squire Sancho Panza on foot, carrying a lance. This woodcut is part of the title page of the first pirated edition of the novel printed in Lisbon in 1605. However, the first edition to include plates representing particular episodes is the first German translation: Don Kichote de la Mantzscha; das ist: Junker Harnisch auss Fleckenland, auss hispanischer Spraach in hochteutsche vbersetzt. Franckfurt, in Verlegung T.M. Götzen, 1648. This edition contains four copperplate engravings.

As regards our featured London edition of 1738, the artistic quality of both the letterpress and the engravings strongly contrast with the low printing standards of most of the seventeenth-century editions. Indeed, the sponsorship of John Carteret, second Earl Granville (1690-1763), enabled the text of the novel to receive the treatment traditionally given to works with the status of a classic. The printing of the text was commissioned to the heirs of a famous dynasty of English publishers: Jacob and Richard Tonson. They were the sons of Jacob Tonson the younger, who in turn was the nephew of Jacob Tonson, the exclusive publisher of John Dryden.

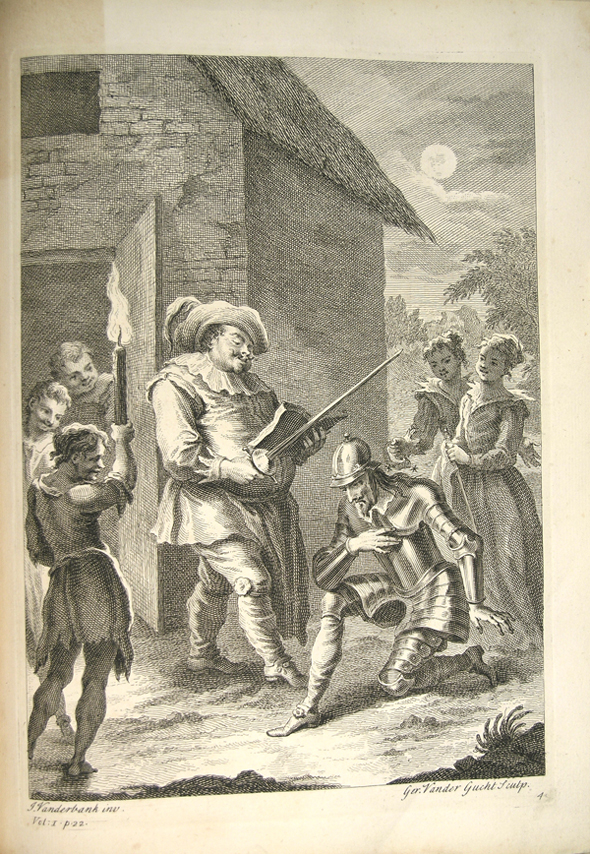

The engravings were designed not only as a faithful companion of particular passages but also as part of an ambitious plan to canonize the novel of Cervantes. According to the Valencian academic J.A. Mayans y Siscar, author of a biography of Cervantes included in this edition, Lord Carteret suggested that a copy of the newly printed novel be added to Queen Caroline's so-called "library of the wise Merlin," which consisted of a collection of "books of invention." Even if this anecdote were a fabrication, Mayans y Siscar is actually echoing the overall philosophy behind this project: to make the novel acceptable to the aesthetic standards of the educated elite, the canon of Neoclassicism. In a general sense, neoclassic literary values are deeply rooted in the rhetorical principles expressed by Aristotle in his Poetics: the representation of reality by means of a literary work should conform to the rules of unity of action, the subordination of characters to that action, and decorum. The concept of decorum is particularly revealing when it is applied to the psychological development of characters: they should behave as expected from their social condition, and according to the temporal sequence of the plot itself.

Any reader familiar with the text of Don Quixote would be skeptical about applying neoclassical standards to the novel. The plot of Don Quixote is characterized by its intrinsic anarchic nature or, some may argue, its freshness: the spontaneity of the characters of the novel contributes to create unpredictable turns in the course of the action. The articulation of the narrative seems to suggest that the author is keeping a "secret dialogue" with his audience in order to please and surprise them by inserting a rich repertoire of jokes, grotesque beatings, sudden changes in the course of the action, stories within stories, and the social transgressions exemplified, for example, by Sancho Panza's ridiculous desire to become governor of the "Ínsula Barataria." In building suspense, Cervantes's creative attitude resembles that of the authors of serial novels in the nineteenth century.

Seventeenth-century readers of all social classes almost exclusively viewed the novel as a burlesque work, as a parody of novels of chivalry as well as an example of popular humor. In contrast, the educated elite of the eighteenth century began to detect both the satirical and moralizing aspect of the novel. A deluxe edition such as the one sponsored by Lord Carteret was probably discussed in the intellectual forums of country houses' libraries, coffeehouses, gentlemen's magazines, and newspapers. In fact, the Carteret edition was well equipped with the necessary critical apparatus to guide the audience towards a neoclassical reading.

In the dedication to the Countess of Montijo, Mayans y Siscar depicts Miguel de Cervantes as a poor old soldier who, ironically, is one of the strongest instruments of the expulsion of the Moors from Spain. Indeed, Cervantes' military past is here used to create a series of symbolic parallels. By comparing the content of chivalry novels with the invading Moors, the novelist's satirical attacks against this type of literature ultimately symbolize the triumph of Christian Spain over Islam. In the biography of Cervantes, which is actually the first printed account of the life of the author, Mayans y Siscar again digresses on the same topic, portraying Cervantes as a hero of neoclassical values fighting against what European intellectuals viewed as the decadent irrationality of the East.

In the preliminary section called "Advertisements concerning the prints," John Oldfield is explicit about the role played by the illustrations, particularly the allegorical frontispiece. In this engraving, Cervantes himself is represented as Hercules Musagetes, avenger of the Muses. Bearing a lyre in one hand, he strides up the path of Mount Parnassus to receive his weapons from a satyr: a club and the mask of Don Quixote. On top of the hill, we can see representations of the grotesque elements of the novel: a giant, a three-headed man, and a multi-headed serpent. As John Oldfield tells us in this "Advertisement," the fact that Cervantes, or Hercules, is wearing the mask of Don Quixote announces that the novelist will be using the elements of satire to enlighten the reader, the final objective being to restore the muses to their seats. In other words, Mount Parnassus signifies society conquered by the fantastic monsters of chivalry novels. Again, the frontispiece echoes the neoclassical interpretation of the novel: the negative example of Don Alonso Quixano represents the dangers of naïve reading.

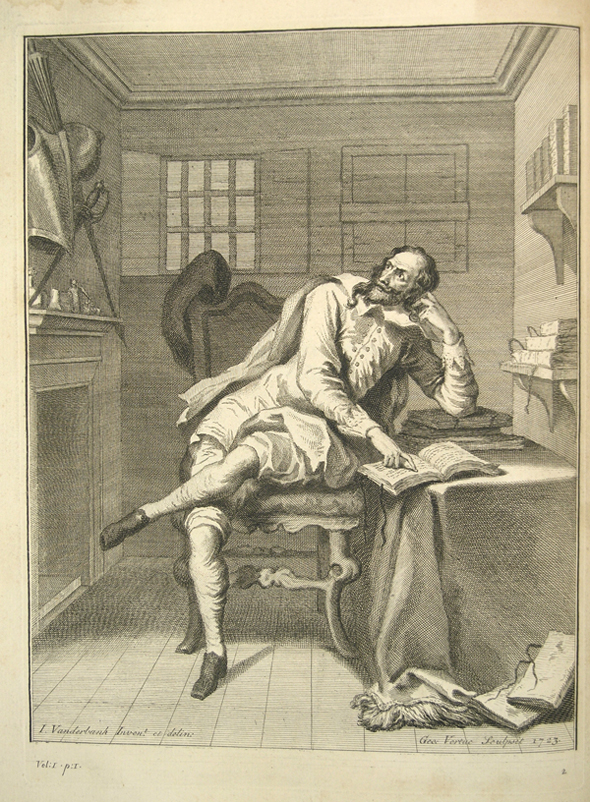

As regards the treatment of the other plates, it is clear that John Vanderbank was always concerned with the human dignity of the characters, an approach clearly suggesting the type of sentimental reading so popular among the middle classes in the eighteenth century. One example may suffice. In the depiction of Don Alonso Quixano reading in his studio -- the first graphic representation of this scene of the novel as previous illustrators used to start the series of plates by inserting the windmill episode -- his madness in only subtlety suggested, merely conveying the gesture of a daydreamer reader.

In view of this neoclassical approach to the content of the novel, it is not surprising that William Hogarth eventually withdrew from the project. Although it is not clear what were the specific reasons for his withdrawal -- one of the causes was perhaps his personal animosity towards William Kent, the painter who designed the portrait of Cervantes -- it is clear that Hogarth's vision of art differed from the overall artistic philosophy manifested in the Carteret edition. While Hogarth defended the notion that art should be a detailed imitation of life, including its satirical and grotesque elements, neoclassical taste preferred an idealized representation of nature based on the aesthetics of the Italian Renaissance. As mentioned above, Hogarth only designed one complete engraving and the figure of the innkeeper in another plate.

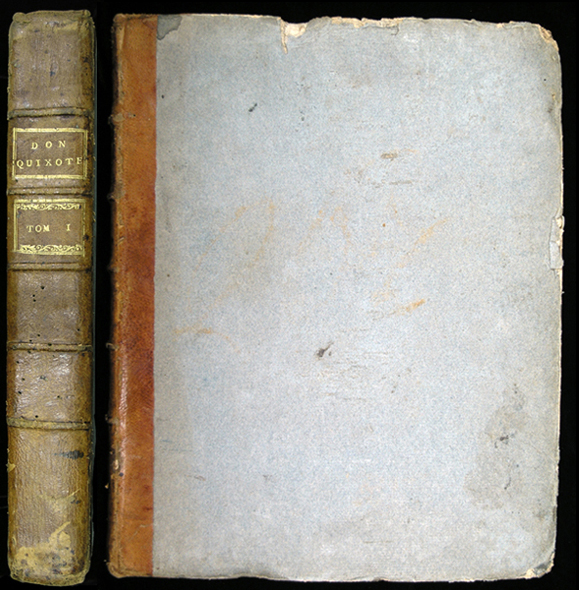

Lastly, a remarkable feature about our copy is the presence of a modest publisher's binding (unopened and quarter-bound in sheep skin over boards) where one would expect that this profusely illustrated quarto edition would deserve a calf binding with gold tooling. Clearly, this choice of binding allowed the publisher to address a wide range of customers, particularly the middle class: a new emerging reading public who probably neglected the scholarly advice of Mr. Oldfield and enjoyed the novel as pure entertainment.

This edition was purchased with funds generously provided by the Friends of the University of Rochester Libraries.

This blog entry was originally contributed by Pablo Alvarez, Curator of Rare Books at the University of Rochester from 2003 to 2010.

Select Bibliography

Aguilera, Francisco. Works by Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra in the Library of Congress. Hispanic Foundation Bibliographical Series No. 6. Washington: Library of Congress, 1960.

Aristotle. Poetics. Ed, and trans. Stephen Halliwell. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1995.

Ashbee, H. S. An Iconography of Don Quixote 1605-1895. London: Printed for the author at the University Press, Aberdeen, and issued by the Bibliographic Society, 1895.

Bennett, Stuart. Trade Bookbinding in the British Isles, 1660-1800. New Castle, Del.: Oak Knoll Press; London: British Library, 2004.

Cervantes Saavedra, Miguel de. Exemplary Novels: Novelas Ejemplares. 4 vols. Ed. B. W. Ife. Trans. B. W. Ife. Warminter, England: Aris & Philips Ltd, 1992

Chartier, Roger, ed. The Culture of Print: Power and the Uses of Print in Early Modern Europe. Trans. Lydia G. Cochrane. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1989.

Hofer, Philip. "Don Quixote and the Illustrators." Dolphin 4, no. 2 (Winter 1941): 135-43.

Jackson, Ian. "Historiographical Review. Approaches to the History of Readers and Reading in Eighteenth-Century Britain." The Historical Journal 47. 4 (2004): 1041-54.

Palau y Dulcet, Antonio. Manual del librero hispano-americano; bibliografía general española e hispano-americana desde la invención de la imprenta hasta nuestros tiempos, con el valor comercial de los impresos descritos. 28 vols. Barcelona: A. Palau, 1948-1977.

Schmidt, Rachel. "La ilustración gráfica y la interpretación del Quijote en el siglo XVIII." Dieciocho 19.2 (Fall, 1996): 203-48.

________. Critical Images. The Canonization of Don Quixote through Illustrated Editions of the Eighteenth Century. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1999.