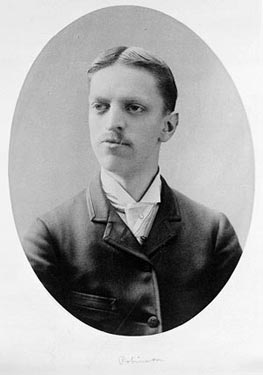

Robinson, Charles Mulford.

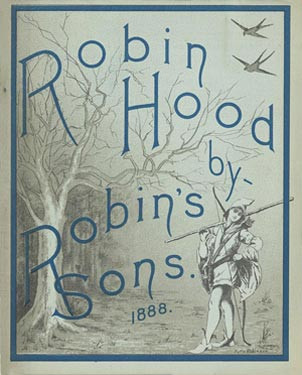

Ye original operetta, in five acts, entitled Robin Hood. Writ by Charles Robinson, musick by Allan G. Robinson. Rochester, NY: E.R. Andrews, 1888.

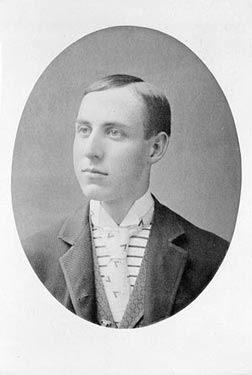

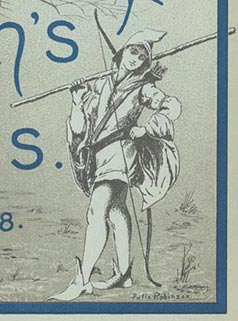

In choosing Robin Hood as a dramatic subject in 1888, University of Rochester sophomore Charles Mulford Robinson (1869-1917; class of 1891) had no obvious theatrical precedents. Though American enjoyment of operetta seems to have grown throughout the century -- Gilbert and Sullivan in particular became a craze in the 1880s, with legitimate and pirated productions, touring companies, and at least seven published scores between 1882-1888 -- Robin Hood seems not to have made it back to the U.S. stage after the 1808 production of a London hit. Robinson's subject was likely determined by a different native tradition, namely Howard Pyle's landmark book, The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood (New York, 1883). Charles Robinson would have been fourteen when the book appeared, and may have been among the first to feel its influence in inventing a powerful and coherent rendition of the myth for modern readers. The link to Pyle's Merry Adventures finds reinforcement in the cover produced by Julia Robinson (Charles' sister, who in 1888 could not have been a student at the University): her image of Robin Hood unmistakably reproduces the figure of the young Robin that Pyle drew at the beginning of his account.

In composing Robin Hood with his classmate Allan G. Robinson (UR, non-graduate of the class of 1890), Charles Robinson inaugurated a new sub-genre, the "collegiate" Robin Hood play. In this he drew upon the inescapable campus mix of the serious and absurd. In addition, he made full use of those traditions, both ancient and contemporary, associated with the theatrical Robin Hood, incorporating carnivalesque, popular, naive, and newly urbane elements, and placing these comfortably in an academic environment of insider allusions and winking innuendo.

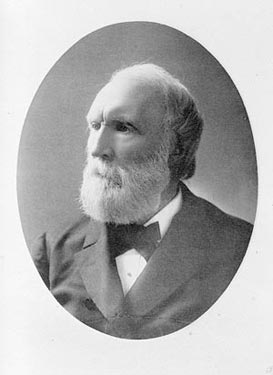

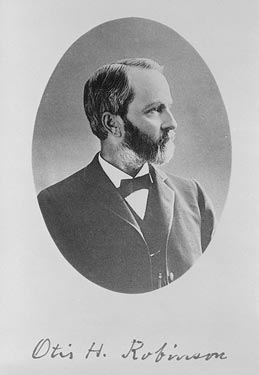

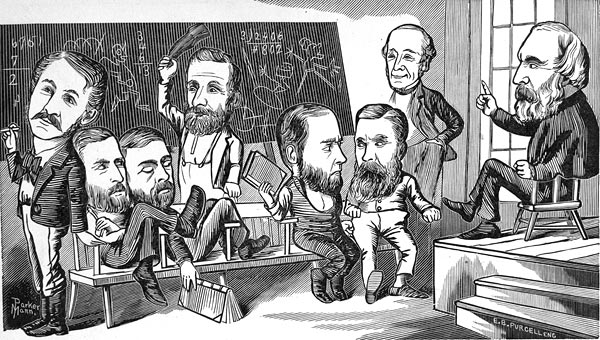

Like the earliest Robin Hood plays, the Rochester Robin Hood is a local and amateur production, community-driven and community-producing. It arises out of its own distinctive, seasonal festival, "May Day" and Commencement, and highlights the licensed misrule and defiance of conventional norms at the core of the Robin Hood mythos. Robin Hood models a topsy-turvydom that smacks not only of Gilbert and Sullivan, but of the earliest play-games as well, having the young and wholesome but powerless Marian and Allan a'Dale undo the corrupt authority of Lord Heatherford through the agency of Robin. Besides the usual crew, the operetta enrolls among the Merry Men all the luminaries of the Rochester faculty: names that currently grace buildings and professorships -- Morey, Anderson, Burton, Gilmore -- turn up as living, if caricatured, personages in the story. Each assumes a distinguishing sobriquet in the Dramatis personae: William Carey Morey's illustrates the Gilbert and Sullivan axiom, "faint heart ne'er won fair lady"; Joseph H. Gilmore "loves the mirth-provoking pun"; President Martin B. Anderson is "The Grand Old Man."

Robinson may have created Robin Hood as a direct response to demands in the mid-80s to make University commencement ceremonies more engaging, and in particular to move from mere speech-making to "exercises." In its account of the Fourth Annual Field Day, the Campus, the student newspaper, reports that the operetta performance, which followed a series of athletic matches in Driving Park, filled the city's New Opera House, and received enthusiastic responses from both students and the larger community. The general public must have greatly outnumbered the students in the audience, since the undergraduate population of the University in 1888 would have been approximately one hundred; the graduating class that year consisted of twenty-two seniors. This remarkable compactness, in comparison to post-World War II college campuses, rendered disciplinary, even class, differences mainly irrelevant, and insured that faculty and students would have an immediate response to this satire of shared, local experiences. A drawing published in the 1877 University yearbook, then as now called the Interpres, portrays the faculty as a restless class of undergraduates, with Morey (first on left) unruly and Gilmore (third from left) bored and apparently dozing. Like the cartoon, the play Robin Hood would have brought instant recognition of the habits and eccentricities of the entire faculty.

Yet, however local the caricatures, many of the individual jokes have a timeless academic cast to them. When Morey comes upon the lovesick Allan a'Dale, he remarks "thou lookest as tho' thou wert learning a French verb"; when Allan explains the source of his unhappiness, the professor replies, "Love is it? Ha, ha, ha! No, William C. Morey was never in love!" The Fool's refusal to divulge information provokes President Anderson to ask, "Why not rattle him, good Robin?" -- that is, pepper him with the sorts of impenetrable questions that make undergraduates break down. Burton demands, "Decline the Roman Empire," and Olds, "What kind of an animal is a parallelopiped?" Mixer calls for him to "Translate into idiomatic German this simple little sentence," which contains a paragraph's worth of dependent and conditional clauses. Having induced the fool to collapse, the witty undergrad Robinson has his counterpart Robin say, "he is but a fool, and you cannot expect as much from him as from a Sophomore." Ultimately, Robin commends the fool to the calming words of one of the faculty-yeomen, noting that academic discourse "is the most effective lullaby in all Nottinghamshire."

Robin Hood by Robin's Sons seems to be the first in a succession of plays produced by students on American campuses as a suitable good-bye to the latest academic year, or more broadly to academic life as a whole upon graduation. In its review of the production, the 1890 Interpres seems to confirm this: "The opera itself is unique, in that it is, as far as we know, the first opera written, composed and sung by college undergraduates." Yale (1912), Wheaton College (1925), and Bryn Mawr (1932) all put on dramatic versions of Robin Hood, although none performed the Robinson version.

Robinson's Robin Hood builds in a wide array of contemporary allusions to literary and popular culture (Shakespeare, Longfellow, as well as advertisements and songs). Politics enters in the characters of the three "villainous villains," notorious anarchists and activists (O'Donovan Rossa, Johann Most, Anthony Comstock) who come off as bumbling extremists rather than outlaw heroes. Robinson demonstrates through these gestures his determination to produce a self-consciously literary work, and he reinforces his seriousness as a writer of satire by noting on the reverse of the title page that he has copyrighted his work with the Library of Congress. Robinson clearly intended Robin Hood, like the libretti of other operettas sold at playhouses, to outlast the moment of performance, and to hold the attention of readers over time. The music is lost to us today, and perhaps was never preserved, despite receiving praise in both Rochester newspaper and Interpres notices.

Extensive, at times daily, reporting in the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle about the Robinson Robin Hood sheds light on the actual production and its status as a local event of some importance. On April 11, 1888, the first mention of the production appeared, but misattributed the libretto to Allan Robinson and the music to Charles. A week later, the credits to both Robinsons were corrected, the libretto had been submitted to the UR faculty, and had "received its unqualified approval." The D&C reporter had also read the script and pronounced it "full of catchy songs, and...free from the crudities usually found in amateur productions." Rehearsals were taking place regularly (May 2); the ballet portion of the production was "said to be very funny while it is free from all objectionable features" and a professional stage manager (M. Stuart Taylor of the Academy of Music) was engaged (May 11). On Sunday May 13, the date of the first performance (of two) was announced, and a cast list printed, with the explanation that "...a glance at the cast of characters given below will give quite as good an idea of the character of the entertainment as a column of description."

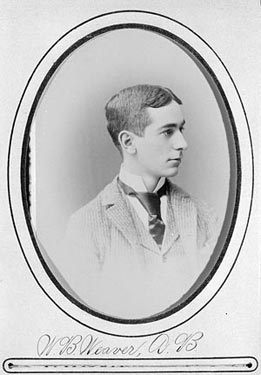

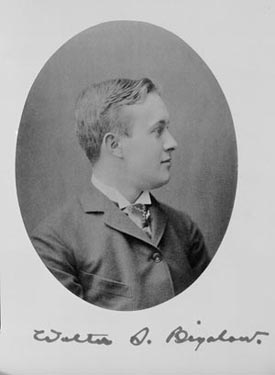

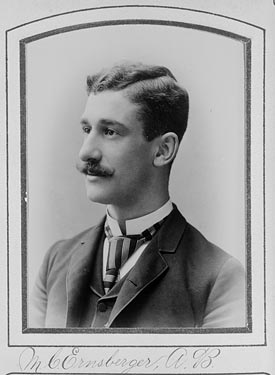

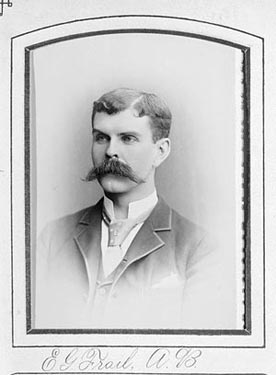

With cast list in hand, it is possible to match faces to the names using student photograph albums in the University of Rochester Archives.