Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus (69-after 122)

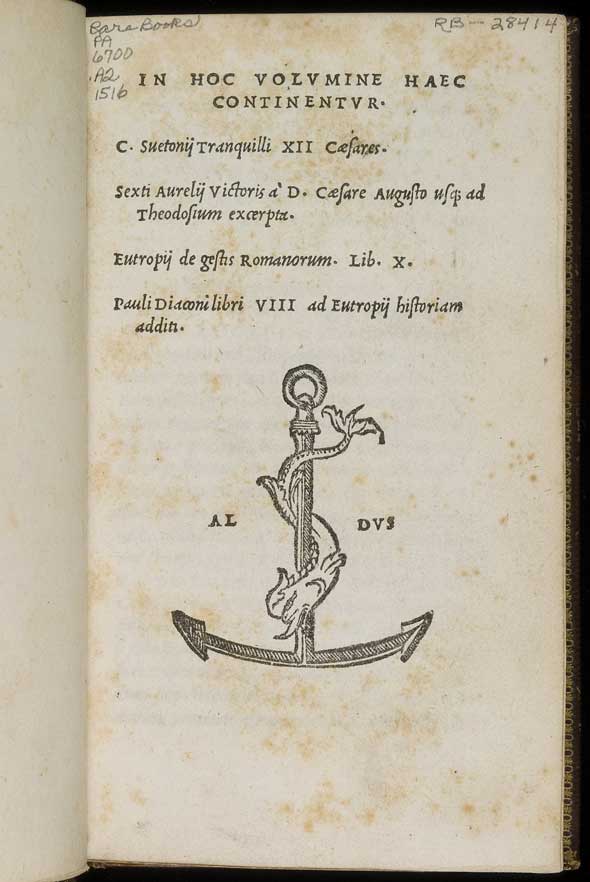

C. Suetonius Tranquilli XII Caesares. Sexti Aurelij Victoris à D. Caesare Augusto usq; ad Theodosium excerpta. Eutropij de gestis Romanorum. Lib. X. Pauli Diaconi libri VIII ad Eutropij historiam additi. Venice: In aedibus Aldi, et Andreae soceri, 1516.

This book is part of the library of Elizabeth G. Holahan (1903-2002).

Our Collection Highlight was printed at the famous Aldine Press of Venice. Following the death of its founder, Aldus Manutius, in 1515, his father in law, Andrea Torresani di Asola, continued to run the printing business until his death in 1529. Eventually, Aldus' son, Paulus Manutius, took over the firm from 1534 to 1574, and Aldus' grandson, Aldus the Younger, from 1575 to 1597. Albeit a pocket-size volume, our book contains four historical works: Suetonius' lives of 12 emperors, Aurelius Victor's imperial biographies, Eutropius' historical breviary, and Paul the Deacon's eight books of Roman history, a continuation of Eutropius' work.

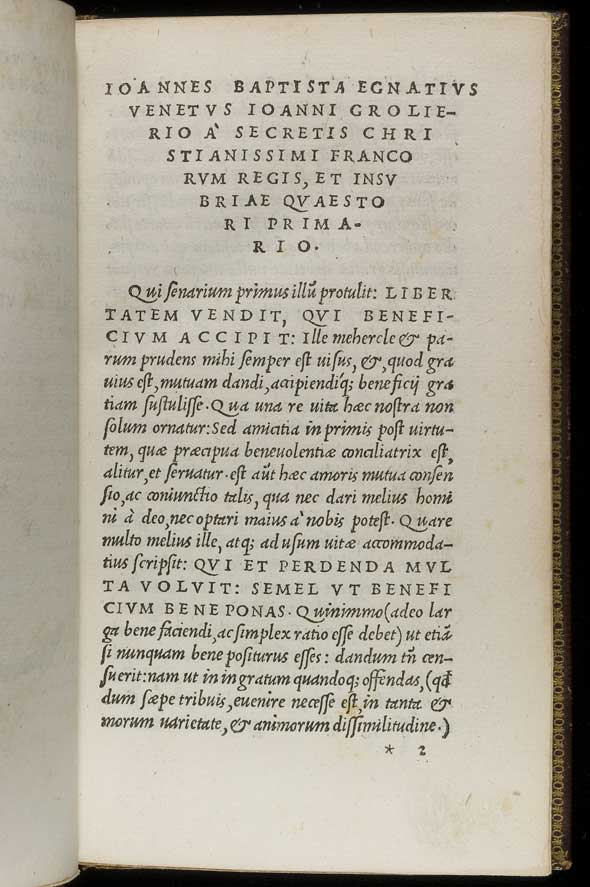

Among the numerous achievements of Aldus Manutius as a publisher and scholar, there are two that mark his place in the history of printing. First, he was successful at introducing a Greek typeface that was both elegant and fairly easy to read. This font was based on the cursive script of a professional calligrapher, Immanuel Rhusotas (Barker, 1985: 47-55). Second, Aldus Manutius was responsible for the massive production of small octavo format volumes like our book of the month, which were printed in a cursive type (italic) reproducing contemporary humanistic scripts. As the reader can appreciate in the images accompanying this essay, the cursive feature was emphasized by its dense appearance and numerous ligatures or tied letters. Specifically, Aldus' italic typeface was cut by Francesco Griffo, who was inspired by the best cursive script of the day, probably that of the leading Paduan scribe, Bartolomeo di San Vito (Lowry, 1979: 141). A vivid testimony of the success of this particular typeface can be found in a letter by Erasmus of Rotterdam. On 28 October 1507, Erasmus wrote Aldus to arrange the publication of his translations of Euripides' Hecuba andIphigenia in Aulis, commenting that an Aldine edition of these translations would give him immortality (letter 207):

I have often privately wished, most learned Manuzio, that literature in both Latin and Greek had bought as much profit to you as you for your part have conferred lustre upon it, not only by your skill, and by your type, which is unmatched for elegance [formulisque longe nitididissimis], but also by your intellectual gifts and uncommon scholarship; since so far as fame is concerned, it is quite certain that for all ages to come the name of Aldo Manuzio will be on the lips of every person who is initiated into the rites of letters (Mynors and Thomson, 1975:131).

As regards the origin and meaning of the Aldine device, the dolphin and the anchor, Erasmus offers a comprehensive explanation in the 1508 Aldine edition of hisAdagiorum chiliades, a collection of Latin essays on the meaning of proverbs taken from classical literature and lexicography. The entry entitled Festina lente (hasten slowly), contains a lengthy digression on the significance of this saying:

It seems to me not too far-fetched to conjecture that it was made out of that expression in the Knights of Aristophanes, speude tacheos, i.e. hasten with haste, so that the person quoting, whoever it was, substituted slowly for hastily. The interest of the idea and the wit of the allusion are enhanced by such complete neatness and brevity, necessary in my mind to proverbs, which should be as clear-cut as gems; it adds immensely to their charm (Phillips, 1967: 3).

Subsequently, in Erasmus' essay the meaning of festina lente is curiously, and anachronistically, linked with examples from ancient literature and riddles. In due course the connections with the dolphin and anchor are established, a symbolism that Aldus himself appropriated.

It is easy to see that this saying pleased Titus Vespasianus, from the evidence of ancient coinage. Aldus Manutius showed me a silver coin, of old and obviously Roman workmanship, which he said had been given him by Pietro Bembo, a young Venetian nobleman, who was foremost in scholarship and a great delver into ancient literature. It was stamped as follows: on one side there was the effigy of Titus Vespasianus with an inscription, on the other side an anchor, with a dolphin wound round the middle of it as if round a pole. This means nothing else than the saying of Augustus Caesar, "hasten slowly" or so the books of hieroglyphics tell us (Phillips, 1967: 5-6).

Overall, Erasmus argues that this printing device is a perfect illustration of Aldus' role as a publisher and scholar. The anchor represents the period of deliberation and scholarly editing before printing a book, the dolphin the speed of its completion.

What was the origin of the Aldine italic pocket books? In the last years of the fifteenth century, many scriptoria were producing small-format codices of the Latin classics, highly decorated, portable, and lacking the apparatus of scholarship. The innovation of these manuscripts lay in applying a small size to a kind of literature traditionally issued in large and imposing formats. Therefore, Aldus was merely introducing a recent manuscript fashion into the printing shop. The small format, lack of commentaries, and cursive type also saved on the cost of paper.

What kind of market was Aldus trying to reach with these portable editions of the classics? Many of Aldus' customers had been exposed to Italian and Latin culture and were men of affairs: diplomats, officers of the state, prelates of the Church, and courtiers. These men would travel around Europe on behalf of princes and republics, spending weeks in their trips by sea and road, and waiting for hours in the hope of an audience. For instance, in a letter dated 1501 the Hungarian councillor, Sigismund Thurzo, thanks Aldus for these octavo editions:

For since my various activities leave me no spare time to spend on the poets and orators in my house, your books—which are so handy that I can use them while walking and even so to speak, while playing the courtier, whenever I find a chance—have become a special delight to me (Grafton, 1999: 186).

Our volume opens with its editor Giovanni Battista Egnazio's dedicatory preface to Jean Grolier, the French bibliophile and diplomat who would become a member of Aldus Manutius' exclusive intellectual circle, the so-called "Aldine Academy." In fact, Grolier acquired over two hundred of the press publications.

The publication of this ambitious edition renewed Egnazio's contacts with Erasmus. Indeed, the Aldine text was published in time for Erasmus to use it in his own edition of Suetonius' Lives, which would be published in Basel in 1518. As a tribute to Egnazio's learning and editorial accuracy, Erasmus hastened to add a second preface, in the form of a letter to the reader, to this 1518 edition. Here I have included the translation of the opening paragraph of this preface (letter 648):

When I had just finished preparing this edition, there arrived a Suetonius printed by Aldus, but with the text emended by Battista Egnazio, a man eminent for both character and learning, two qualities needed equally, in my opinion, by anyone who undertakes to edit or comment on the production of antiquity. For my part, I bear the death of my friend Aldus with greater resignation when I see that in this department of restoring the text of the classics he has a successor capable of overshadowing the dead man's reputation, distinguished as he was in his own right, if one can use the word "overshadow" of excellence by excellence outstripped (Mynors and Thomson, 1979: 98).

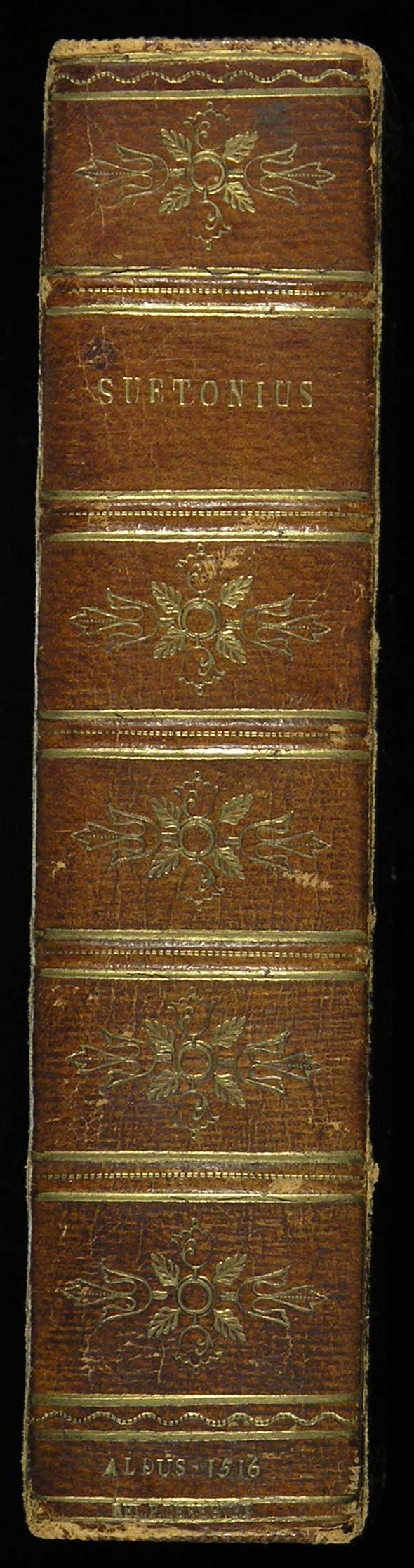

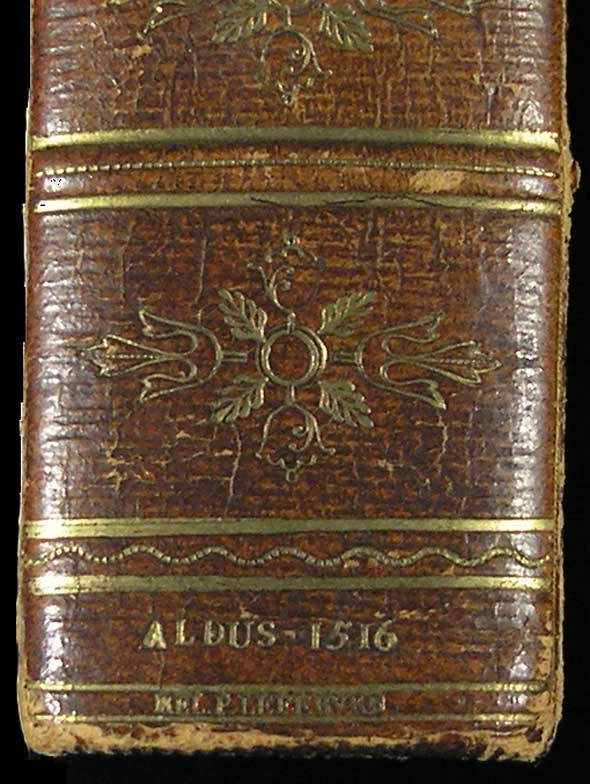

Finally, we should mention an interesting feature about the binding. On the lower section of the spine we can read the name P. Lefebvre, a French binder working in Paris during the first half of the nineteenth century (Ramsden, 1950: 123). He bound this copy in straight-grain morocco—the natural grain of the goatskin has been artificially modified.

This blog entry was originally contributed by Pablo Alvarez, Curator of Rare Books at the University of Rochester from 2003 to 2010.

Selected Bibliography

Barker, Nicolas. Aldus Manutius and the Development of Greek Script and Type in the Fifteenth Century; with original leaves from the first Aldine editions of Aristotle, 1497; Crastonus' Dictionarium Graecum, 1497; Euripides, 1503; and the Septuagint, 1518. Sandy Hook, Conn.: Chiswick Book Shop, 1985.

Barker, Nicolas et al. The Aldine Press: Catalogue of the Ahmanson-Murphy Collection of Books by or Relating to the Press in the Library of the University of California, Los Angeles. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

Erasmus of Rotterdam. Erasmi Roterodami Adagiorum chiliades tres, ac centvriae fere totidem. Venice: Aldus Manutius, 1508.

________. Opvs epistolarvm Des. Erasmi Roterodami. Ed. P.S. Allen. Vol. 1. 1484-1514. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1906.

________. Erasmus on his Times: A Shortened Version of the "Adages" of Erasmus. Trans. Margaret Mann Phillips. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1967.

________. The Correspondence of Erasmus. Letters 142 to 297, 1501 to 1514. Vol. 2. Trans. R.A.B. Mynors and D.F.S. Thomson. Annot. Wallace K. Ferguson. Toronto & Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1975.

________. The Correspondence of Erasmus. Letters 594 to 841, 1517 to 1518. Vol. 5. Trans. R.A.B. Mynors and D.F.S. Thomson. Annot. Peter G. Bietenholz. Toronto & Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1979.

Grafton, Anthony. "The Humanist as Reader." In A History of Reading in the West. Ed. Guglielmo Cavallo and Roger Chartier. Trans. Lydia G. Cochrane. 179-212. Amherst & Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999.

Lowry, M.J.C. The World of Aldus Manutius: Business and Scholarship in Renaissance Venice. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1979.

________. "Giambattista Egnazio of Venice, 1478-4 July 1553." In Contemporaries of Erasmus: A Biographical Register of the Renaissance and Reformation. 3 vols. Ed. Peter G. Bietenholz and Thomas B. Deutscher, 424-5. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1985.

Ramsden, Charles. French Bookbinders, 1789-1848. London: Printed for the author by L. Humphries, 1950.

Renouard, Antoine Augustine. Annales de l'imprimerie des Alde, ou, Histoire des trois Manuce et de leurs editions. Paris: A.A. Renouard, 1834.

Ross, James Bruce. "Venetian Schools and Teachers, Fourteenth to Early Sixteenth Century: A Survey and a Study of Giovanni Battista Egnazio." Renaissance Quarterly29. No. 4 (Winter, 1976): 521-66.