John Michael Wright (ca. 1617-ca. 1694)

Raggvaglio della Solenne Comparsa, fatta in Roma gli otto di Gennaio MDCLXXXVII. Rome: Domenico Antonio Ercole, [1687].

The ownership inscription of the title page along with the fact that this book was published to promote the cause of the Catholic faith in England suggest that our copy originally belonged to Henry Waldegrave, first Baron Waldegrave (1661-1690) and Lord Lieutenant of Somerset from 11 August 1687 to 24 January 1689 (one can easily read the two Ls of the signature and the LD as a shorthand for "Lord"). Being from a strong Roman Catholic family, Henry married Lady Henrietta Fitzjames (1666/7-1730), the eldest illegitimate daughter of James, then duke of York, later King James II, and of Arabella Churchill (1649-1730), the sister of John Churchill, later first duke of Marlborough (1650-1722). A firm supporter of the Catholic King James II, Henry was made Baron Waldegrave of Chewton in 1686, and a year later he was appointed comptroller of the royal household. In 1688 he went as the King's envoy to France and remained there in exile following the so-called Glorious Revolution, or the overthrow of James II. Henry died at Châteauvieux, St Germain-en-Laye in 1690. His wife Henrietta later married Pierce Butler, third Viscount Galmoye and Jacobite earl of Newcastle (1652-1740).

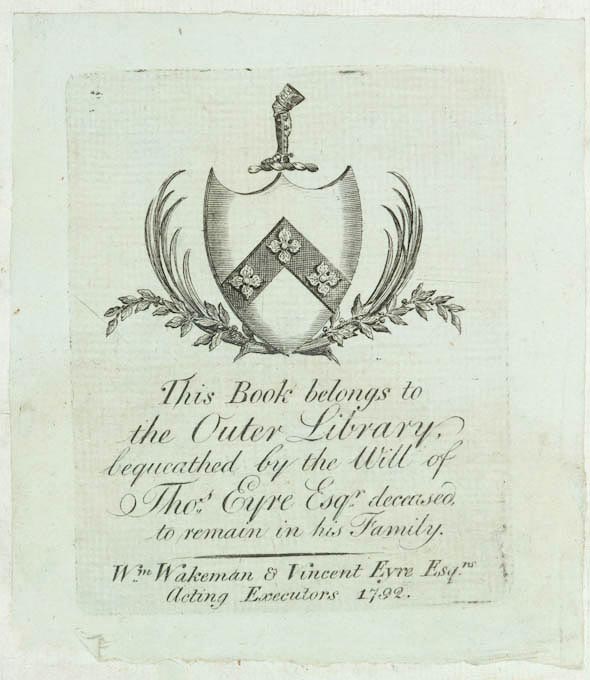

Nevertheless, the book-plate on the front pastedown paper tells us a more complex tale about the provenance of this volume. As I will argue, it seems clear that subsequent ownership of our volume can only be explained by a Catholic connection.

The significance of this book-plate must be studied within the origins and dispersal of the library of Sir Thomas Tempest of Stella (county of Durham), fourth baronet of the family (1662-92)—a number of medieval manuscripts from this library ended up in the Harleian collection of the British Library (Wright, 1972: 325). Aside from displaying his name, "Sr Thomas Tempest Baronet", many manuscripts and printed books in Sir Thomas's library also show ownership marks from the libraries of the Benedictine monastery and Priory at Durham. The obvious question is: How did these books end up in his private library?

The forebears of a branch of the Tempest family settled at Lanchester, county of Durham, and Holmside Hall, north of it, from the fifteenth century, and at Stanley, in the north-west section of the county, from the early sixteenth century. Nicholas Tempest of Lanchester and Stanley, who died in 1538/9, married Anne Marley of Gibside. One of her brothers was Stephen Marley, a monk of the Benedictine monastery of Durham who was sub-prior at the suppression of the monastery in 1539. Nicholas Marley was likely another brother, and their names as owners, as monks or later as canons of the new Durham Cathedral, appear in many of the manuscripts and printed books which eventually formed a substantial part of the library of the fourth baronet, Sir Thomas Tempest. Both Stephen and Nicholas Marley suffered considerably under the religious reformation of Henry VIII, Edward VI, and Elizabeth I (Tempest, 1895: 5-14; Surtees, vol II, 1820: 271, 325-7; Doyle, 1984: 83-6).

While many members of the Tempest family converted to the Protestant faith, it is also true that others stubbornly refused to do so. For instance, Robert Tempest of Holmside, cousin of Thomas Tempest of Stanley (the son of Nicholas Tempest of Lanchester and Stanley), along with his son Michael were involved in the revolt of the northern earls, the unsuccessful uprising against Elizabeth I by Catholics of Northern England in 1569. If Nicholas, Thomas's first son, claimed to have accepted the new faith, his own wife was imprisoned for her recusancy. Nicolas's eldest son, Thomas, was publicly declared a "no recusant", but his son Richard became convinced of the Catholic faith. In turn, Richard sent his son Thomas to the English College at Douai, a Catholic seminary located in Northern France. This is the Thomas who, as mentioned above, would become fourth baronet and add his name to the books of the family library. Clearly, the Catholic branch of the Tempest family decided to keep those books that represented not only a long monastic tradition, and still useful from the theological point of view, but also that symbolized old religious alliances (Doyle, 1984: 87-8).

Sir Thomas died in 1692, and his son and heir having died abroad six years later was succeeded by his sister Jane, who married Lord Widdrington. By 1700 there was a Benedictine chaplain at Stella Hall, which was served by this order until 1732. Before her death in 1714, Jane had made the necessary arrangements to secure an endowment for a permanent priest at Stella, and when her son Henry died in 1774, the family estates were inherited by Thomas Eyre of Hassop (Derbyshire), his nephew. In turn, Thomas appointed the Rev. Thomas Eyre for service at Stella, where he stayed until 1792, when his patron died. It is very likely that Thomas Eyre of Hassop himself decided to remove many of the books to Hassop, where he established two libraries, an Inner and an Outer Library. Since our copy does not have the inscription "Sr Thomas Tempest Baronet", it must have been added to the "Tempest family collection" sometime after Sir Thomas's death in 1692. Thomas Eyre of Hassop established that the Inner Library be bequeathed to the Bishop of Midland District, and the Outer Library, as our book-plate indicates, was supposed to remain in the family. However, part of this library was eventually sold through the antiquarian market as shown by our copy, purchased by Elizabeth G. Holahan (1903-2002), and donated to our collection after her death (Doyle, 1984: 89-90).

It seems that the Ragguaglio was added to the Tempest library for the book's historical and religious significance. Apart from the fact that it belonged to a faithful supporter of the Catholic King James II, this title is a record of the last serious attempt to reestablish the ancient faith in England.

The diplomat and Catholic apologist Roger Palmer, earl of Castlemaine (1634-1705), was a member of a Catholic elite who formed James' secret council. When the King decided to restore diplomatic relations with Rome, he appointed Castlemaine as ambassador to the curia. The new envoy arrived at Rome 13 April 1686, although he did not enter the city officially until 8 January 1687. The delay was due to the illness of Pope Innocent XI as well as the extremely elaborate preparations for a ceremonial entrance, which Castlemaine thought appropriate to display the might of the British monarchy. The Scottish portrait-painter, John Michael Wright (bap. 1617, d.1694), was appointed as steward to Castlemaine, probably because of his knowledge of Rome and the Italian language. Wright coordinated the construction of carved coaches as well as the design of all the attendants' costumes and decorations that made up the procession.

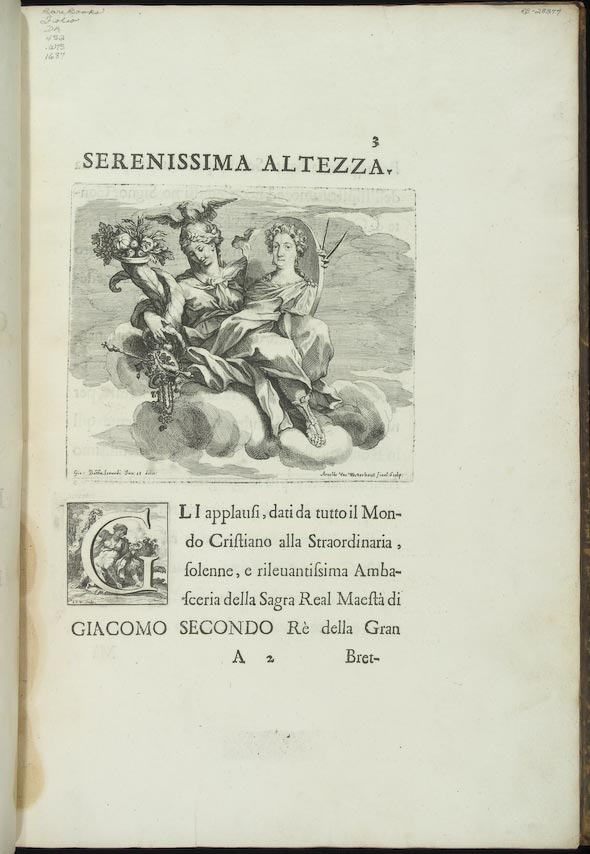

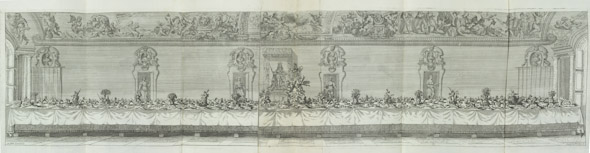

Wright also arranged a banquet of 1000 guests, with tables covered with sugar sculptures, in the Palazzo Doria Pamphilj. Shortly after this extraordinary series of events, Wright published the Ragguaglio, a sumptuously illustrated book recording numerous details of the Castlemaine embassy and its reception at Rome. The engraver Arnold van Westerhout followed the originals drawings by Giovanni Battista Lenardi. Wright wrote the text, which he dedicated to the duchess of Modena, and an English translation was published in 1688.

This blog entry was originally contributed by Pablo Alvarez, Curator of Rare Books at the University of Rochester from 2003 to 2010.

Selected Bibliography

Doyle, A. I. "The Library of Sir Thomas Tempest: Its Origins and Dispersal." Studies in Seventeenth-Century English Literature, History, and Bibliography: Festschrift for Professor T.A. Birrell on the Occasion of his Sixtieth Birthday. Ed. Jan Aarts and Willem Meijs (Costerus, 46, 1984): 83-93.

Wright, Cyril Ernest. Fontes Harleiani. A Study of the Sources of the Harleian Collection of Manuscripts Preserved in the Department of Manuscripts in the British Museum.London: The Trustees of the British Museum, 1972.

Surtees, R, George Taylor, and James Raine. The History and Antiquities of the County Palatine of Durham. 4 vols. London: J. B. Nichol and Son, 1816-1840.

Tempest, E. Blanch. "Tempest of Holmside, County Durham." The Northern Genealogist (1895): 5-14.