Special [spesh-uhl], adjective: of a distinct or particular kind or character; held in particular esteem.

Rare [rair], adjective: seldom occurring or found; marked by unusual quality, merit, or appeal.

Unique [yoo-neek], adjective: existing as the only one or sole example; having no like or equal.

These words broadly describe the materials and items that constitute three areas within the University of Rochester Libraries: The Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation (RBSCP) in Rush Rhees Library (River Campus Libraries), the History of Medicine section in the Edward G. Miner Library (University of Rochester Medical Center), and the Ruth T. Watanabe Special Collections at the Sibley Music Library (Eastman School of Music).

The University community and general public don’t often get to see the various treasured items held by these libraries, let alone have someone give a detailed explanation of what they are and their history and historical relevance. But thanks to the Friends of the University of Rochester Libraries (FURL), this exact scenario will occur three times in the next seven months.

Rush Rhees, Miner, and Sibley Libraries will be showcasing some of their most extraordinary and valued materials on the following dates:

- October 29, 2002: RBSCP at Rush Rhees Library

- February 25, 2023: Ruth Watanabe Special Collections at Sibley Library

- April 15, 2023: History of Medicine section at Miner Library

All dazzle, no razzle

The show-and-tell events are the brainchild of FURL member Hal Kanthor ʼ66M (MD), who thought it would be nice for members to see some of the items the libraries purchased with FURL’s help.

Each year, FURL asks the University libraries—including the Charlotte Whitney Allen Library at the Memorial Art Gallery—to submit project proposals, which can include books or manuscripts and items that wouldn’t be found on shelves, like a table or shelves. “We try to be equitable,” says Kanthor, chair of FURL’s distribution committee, which makes recommendations on what projects receive funding. “We try to find something we can fund at each library, and sometimes a library’s request is for non-bookish materials because that’s what they need. So we help where we can, but we have to work within our budget.”

Seeing the fruits of FURL’s funding is only partly why Kanthor initiated the event series. He also wanted to convey the library’s wealth of materials to a large audience. “Some of the real treasures in these departments are things we have not funded but will dazzle those who attend,” he says.

Martin Zemel ʼ63, ʼ65W (MA), P’02, FURL treasurer and distribution committee member, adds that the events are also a matter of pride. “All libraries tend to be on even ground in terms of what they have in their collections,” he says. “It’s the rare books departments that distinguish one university from another. And we’re very proud of ours, and we want the community to see why.”

Free preview

Admittance to each department’s showcase is $25 (or $60 for all three) and limited. (Reserve your spot with Kim Osur, development manager for the River Campus Libraries.)

Still unsure about these events? Prepare to be dazzled. Here’s a sample of what will be shared at the October 29 event.

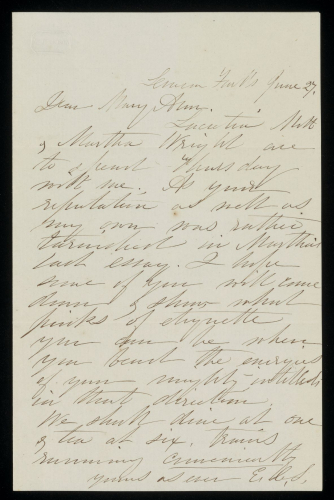

Letter from Elizabeth Cady Stanton to Mary Ann [M’Clintock]

with Autumn Haag, assistant director of RBSCP

In the summer of 1848, pioneering feminist Elizabeth Cady Stanton, living in Seneca Falls, New York, wrote to “Mary Ann,” presumably Mary Ann M’Clintock, a friend in the neighboring village of Waterloo. Stanton wrote:

Dear Mary Ann,

Lucretia Mott & Martha Wright are to spend Thursday with me. As your reputation as well as my own was rather tarnished in Martha’s last essay, I hope some of you will come down & show what pinks of etiquette you can be when you bend the energies of your mighty intellects in that direction. We should dine at one & tea at six. Trains running conveniently.

Yours as ever, E.C.S.

The letter was dated June 27, putting it in the mail just a couple of weeks before these women met to plan the Seneca Falls Convention that would take place on July 19 and 20, 1848. Stanton’s tongue-in-cheek comments about reputation are likely a reference to Wright’s “Hints for Wives,” a satirical essay about the expectation for women to be obedient to their husbands.

Director’s commentary:

“We have some really amazing material in our collections related to the women's rights conventions in Seneca Falls and Rochester in 1848, but not a lot of correspondence that predates them. Most of our [Susan B.] Anthony and other women’s rights correspondence is a little bit later, so to have a letter from the summer of 1848 fills a gap in our collection. Letters like this from Elizabeth Cady Stanton are incredibly rare and hard to find in private or academic collections.

Stanton is always perceived as this kind of grandmotherly figure. Yet, here, she is 32 [years old], a young mother, and is sort of sarcastic and playful with Mary Ann as she invites her to dinner and tea. And this is in between all of this really important work. She and the other women, including those in this letter, had periods in which they were working non-stop, brainstorming, writing, and having meetings like this with like-minded women to generate something really big.

So, this is just a tiny little piece of a bigger picture that helps us see the women in this movement as human beings. It offers a glimpse into what they were doing and what their lives were like on the other side of their activism.” —AH

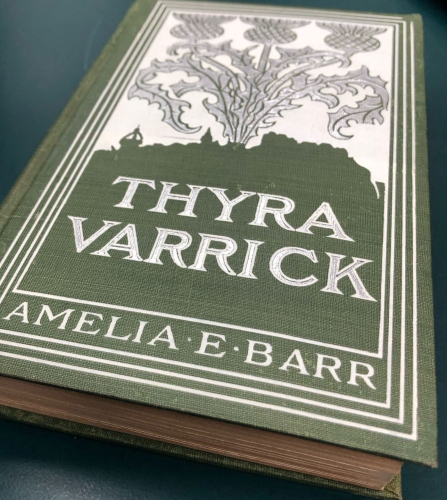

Thyra Varrick by Amelia Barr (published and manuscript editions)

with Jessica Lacher-Feldman, exhibitions and special projects manager for RBSCP

British novelist Amelia Barr (1831–1919) is seldom read today but was extremely popular in her lifetime.

Barr didn’t start writing until her mid-50s, and it wasn’t because inspiration struck. After losing her husband and most of her children to yellow fever, writing was a matter of her and her remaining children’s survival. As a working writer, she was prolific. In her autobiography, All the Days of My Life, Barr acknowledges an undefined list of work that includes short stories, poems, and essays that she barely remembers: “I have forgotten the very names of this vast collection of work and I never kept any record of it. Indeed, only some chance copy has escaped the oblivion to which I gave up the rest. They kept money in my purse; that was all I asked of them.”

Thyra Varrick is a love story. According to a New York Times book review from 1903, in 10 seconds, Scottish soldier Major Hector MacDonald “incontinently succumbs to the charms of lovely Thyra Varrick, daughter of a sea Captain and fisherman.” And although Thyra falls for Hector, it’s not an instant happy ending.

Curator’s commentary:

“Thyra Varrick was a source of pride for Barr, who describes it in her autobiography as “a great favorite, for it was the initial story of The Delineator.”

Before it was released as a bound volume, the story was first serialized in The Delineator, an American women’s magazine known for publishing clothing patterns, photos, and drawings of embroidery and needlework, and articles on home décor. The magazine published Barr’s story in pieces between September 1902 and May 1903, encouraging readers to continue to buy the magazine to see what happens next.

I love that Thyra Varrick started in The Delineator. In a magazine largely dedicated to women, their work, and their creative outlets, I can’t think of an author for women to read at that time that would be more fitting than Barr.

The first edition that was published in its entirety was released in 1903. The book is appropriately adorned with stylized thistles, a well-known symbol of Scotland (where the story is set). We have multiple editions of the novel, and they are beautiful examples of publisher bindings from the turn of the 20th century.

Amelia Barr is a fascinating example of self-sufficiency and survival despite oppression. Her journey and work are sources for one to gain a deeper understanding of women and work, creative expression, and the history of readership and authorship.” —JLF

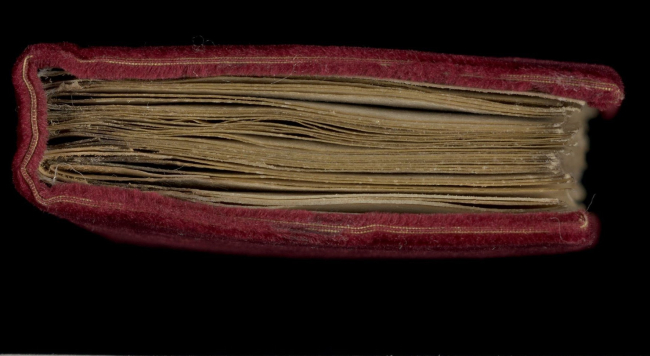

Devotional Miscellany

with Anna Siebach-Larsen, director of Rossell Hope Robbins Library

and the Koller-Collins Center for English Studies

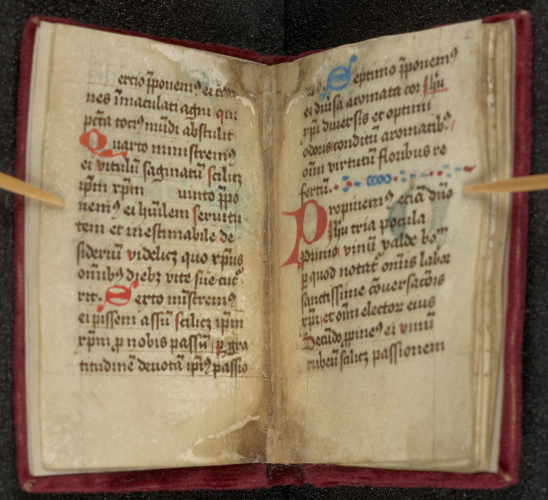

In the later Middle Ages, a religious movement called the “Devotio moderna” was especially popular in areas that make up today’s Netherlands and Germany.

The reforming movement was popular among laypeople, friars, and others who were not necessarily aligned with the hierarchy and bureaucracy of the Catholic Church. Participation in the movement manifested in the form of booklets containing individuals’ favorite parts of “best-selling” religious texts—think medieval theological Pinterest. These booklets would essentially be the foundation of their religious practice, devotion, and life.

Robbins Library has a pocket-sized example of one of these devotional miscellanies (in terms of size, it’s the smallest in Robbins’ collection) from the mid-15th century. It contains Thomas à Kempis’s Libellus Spiritualis Exercitii, excerpts from the Imatatio Christi, excerpts from Conrad of Saxony’s Speculum beatae Mariae virginis, and other writings from philosopher Robert Grosseteste and early Church fathers.

Commentary from the director:

“What makes this manuscript so valuable is how common it is. It’s a great representation of what the average middle-class person would have been really interested in at this time. It’s the kind of personal religious book that, because of its size, someone might have carried around in their pocket wherever they went. The excerpts and writings within a book of this nature were likely to be the kind that the owner would have a connection to that was deeply personal and emotional.

Most individuals’ relationship with religion was facilitated by a priest or similar 'authority figure' who shaped their beliefs. During the reformation period a person’s relationship with God wasn’t as rigid, and grew more undefined with the popularity of the devotional texts. Those miscellanies grew more favorable as the broader population’s literacy, ability to afford books, and desire to direct their own religious experience.

One thing that is really important about this is that it combats the narrative that no one in the Middle Ages owned books or knew how to read. And because the owners of these books were passionate about the contents, they helped push their beliefs and interests across social structures and inspire change.

The kinds of religious movements and religious trends that this manuscript was born from effectively paved the way for Martin Luther and Protestantism.” —ASL ∎

If you’re interested in or have questions about the FURL event or becoming a member of FURL, contact Kim Osur at kim.osur@rochester.edu. Have questions about one of the pieces above? Email Autumn Haag, Jessica Lacher-Feldman, or Anna Siebach-Larsen.

Enjoy reading about the University of Rochester Libraries? Subscribe to Tower Talk.